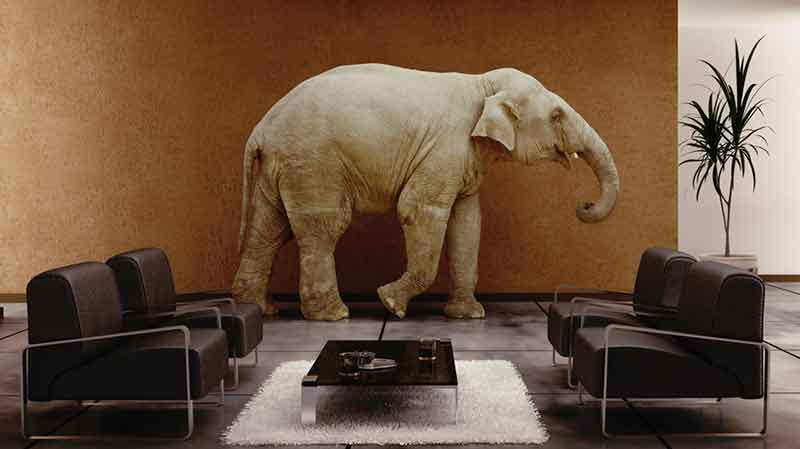

Much has been written over the years about the discipline of process analysis and process improvement. There is a vast body of knowledge spanning techniques, standards and methodologies—and there are many resources that can be drawn on (including many useful articles and white papers on sites like this one!). Undoubtedly, adopting these kinds of best practices help organizations to design slicker, quicker and more customer-focused processes. Yet defining an efficient, effective and shiny new process is one thing—implementing it and making it stick and ensuring it achieves the planned benefits is quite another. So often, processes are redesigned with the best of intentions—but when they are implemented, they don't quite work as expected. Additional and unforeseen steps are shoe-horned into the process by people operating the processes out of necessity, and efficiency and effectiveness is reduced. These kinds of failed improvement projects become the proverbial 'elephant in the room'. Everyone knows they haven't gone to plan, but they are rarely mentioned.

One significant contributing factor to failures like this can be a lack of engagement with the relevant people within our organizations. As practitioners of change, it's key that we work with a wide range of our stakeholders to understand the business outcomes that our companies are aiming for. A process of any description is, in many ways, a means to an end—it helps us achieve a goal, output or outcome. Yet different stakeholders will want to achieve different things from that process—and sometimes these needs and wants might conflict. Uncovering these areas of disagreement early, discussing them and working to gain consensus is extremely beneficial. This builds engagement from the very beginning, makes it much more likely that we'll foresee issues, and makes it much more likely that the process will deliver the benefits and outcomes that we are aiming for.

Understanding what our stakeholders want to "get out" of a process requires us to think broad and wide. Let’s take an example: Imagine we are improving a sales process for a call center that sells tickets for concerts and sporting events. Perhaps an initial scan of our stakeholders would uncover the following perspectives:

Customer: Wants to order the best ticket at the cheapest price with a minimum of fuss (and a minimum of waiting).

Call center operator: Wants a process that allows tickets to be sold quickly and efficiently, with systems that minimize errors and double-keying. Also wants key information at her/his fingertips.

It would be easy to stop here, and perhaps we could create a process that met the needs of these two stakeholders. However, the process might not "Stick". Other stakeholders might have other implied requirements, and we ignore them at our peril. For example:

Call center manager: Needs regular statistics and management information to lead and manage the team (or else he/she will 'tweak' the process, introduce manual steps, spreadsheets and databases to capture the data manually—adding additional steps which will ‘nibble away’ at the efficiency of the process).

Compliance Manager: Needs to ensure that all sales are compliant (or else she/he will introduce additional scripts that will be 'shoe-horned' into the process, perhaps requiring the call center operator to navigate through additional manuals, network drives and documents).

Printing/Dispatch: Need clear address validation up-front (or else exceptions are created which require the call center agents to make outbound calls, disrupting their day and creating additional work).

Marketing Manager: Needs a wide range of data on which tickets sell for which types of event; how quickly popular events sell out and so on (or else they will need the call center agent to collect the data manually on an additional data capture form).

We could go on—however, as this hypothetical example shows, it would be very easy to be inadvertently blinkered and focus on a narrow stakeholder group. Engaging a wider community of stakeholders early will help avoid nasty surprises later. It'll build buy-in, as everyone's voice will be heard. It provides the opportunity to resolve conflict and accelerate our process analysis and redesign efforts.

In summary: By casting the stakeholder net wide, we build engagement from the very outset, ensure key requirements are captured, and can co-create a process that is much more likely to ‘stick’.

.webp)