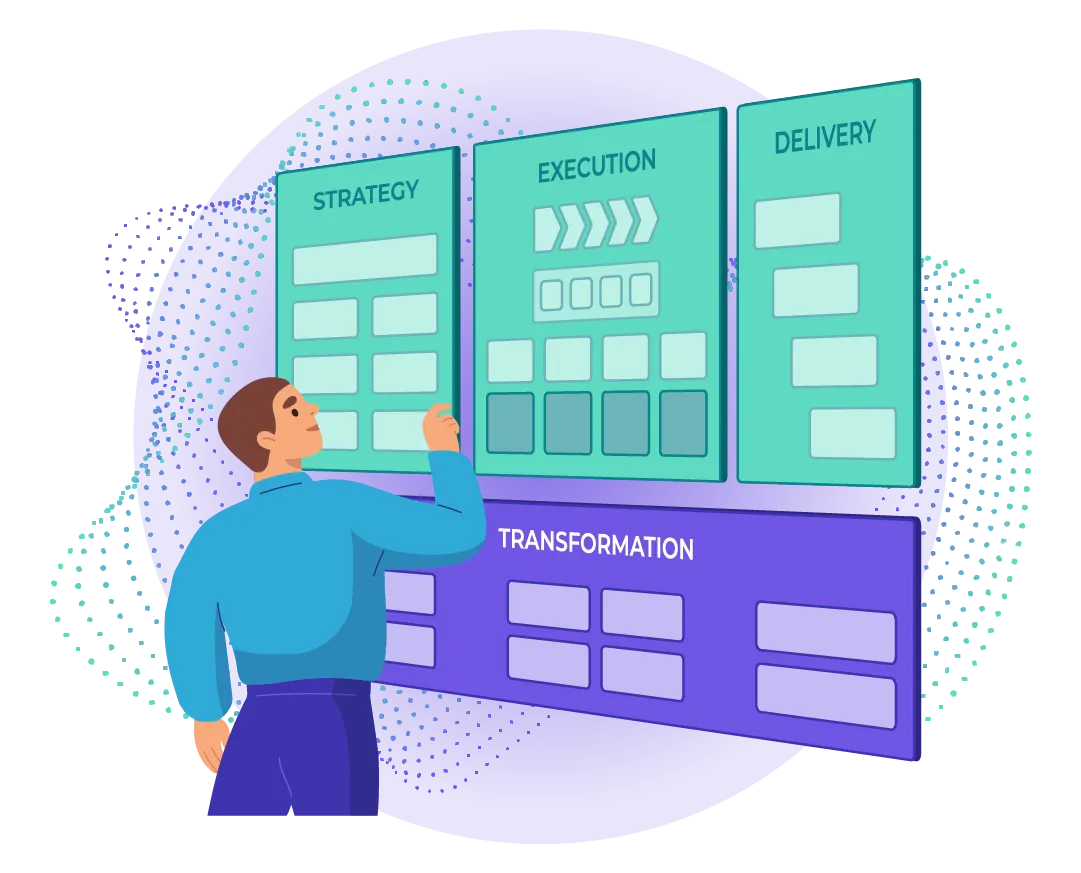

To put it another way, before embarking on a project, ask, “what are you hoping to achieve by modeling?” The answer to this question effectively denotes what it is that you want to model.

What Should We Be Modeling?

With little agreement on even basic definitions, it is perhaps unsurprising that commonalities between different enterprise architecture functions are, at times, sparse. They can comprise an array of teams, people, tools and processes, and exist in almost any location, industry or sector.

Nonetheless certain similarities do persist. One of the most prevalent concerns for new initiatives is where to begin. This dilemma is almost always coupled with the questions: “How far do we go?”, and, “What level of detail should we be modeling to?”

When answering any question of this ilk, and specifically in relation to modeling, we must remember models are there solely to offer insight. If there is no insight to be derived from drilling into increasing granularity, then what is the benefit? Indeed, such an exercise will merely add to complexity, cost and time.

Furthermore, there is an issue of basic practicality. If you were so inclined, you could model every single application function and every step in every part of every process. You could model the individual tables, the ports in each hub, and trace through end-to-end. Maybe after 20 years, you'd be finished documenting your current state.

Knowing this information, however, only provides guidance on what not to do. It does not provide a magic formula as to what you should do. There's a certain sweet spot for how much detail to include. While it is likely that one day we'll reach a point where there's a consensus and established best practice, we're not there yet. Attempting to work this out is the forte of enterprise architects and where they bring value to the business; helping focus your efforts, and knowing where to direct resources, funds and staff.

The Art of Enterprise Architecture

In enterprise architecture, we should constantly ask, ‘why are we doing this?’ This simple reflective question must be a beacon in the often gloomy plethora of conflicting and ambiguous information.

To put it another way, before embarking on a project, ask, “what are you hoping to achieve by modeling?” The answer to this question effectively denotes what it is that you want to model.

For instance, if the objective is to attain regulatory compliance, the key is to know which areas of the organization are affected, and how regulations affect the processes you execute. Consequently, the logical decision would be to model processes, the regulations that exist, and how they correlate. Anything else is at best unnecessary and at worst an overcomplication.

Alternatively, if the challenge facing the enterprise is to move away from the siloed IT currently in place as a result of acquisitions, it requires identifying which applications are duplicating functions, to enable a consolidation. As such the enterprise architecture team should map applications to functions (and ideally to business processes).

Ultimately models are not an end in themselves, and we do not undertake enterprise architecture for enterprise architecture’s sake. In recognizing the types of analysis we want to run, we will understand the level of detail we want in our models.

.webp)